As a little prince with a pageboy haircut, Don Prospero Colonna di Paliano, Prince of Avella, played among the Roman statues and laurel and box hedges in the magnificent terraced gardens of his family’s 14th-century palace. He and his siblings ate pizza and pasta with their grandmother, Princess Isabelle, who was for decades a leading doyenne in Roman society, in a dining room wallpapered in sumptuous red silk. They raced under dripping Murano chandeliers and oriental marble pediments inlaid with the family’s coat of arms.

But the Colonna Gallery, a grand hall adorned with 270 paintings, intricate giltwork, painted mirrors, monumental tables, and plenty of other breakable things, was absolutely off-limits. “We were not allowed to come here,” the low-profile prince, now white-haired and 63, tells T&C, clasping his hands and leaning back, apparently so he can chuckle at a polite distance.

The standard-bearer of a noble family that has produced one pope, 22 cardinals, 10 bishops, and a mayor, Don Prospero is now eager for the public to visit, and then appreciate on social media, a patrimony that for centuries has dazzled heads of state and military leaders—and some world class coquettes, including one who helped inspire its creation.

In 1661 the Colonna prince Lorenzo Onofrio commissioned the gallery not only as a showcase for the family’s astonishing art collection but as an assertion of potency amid rumors that his comely wife, Marie, was the paramour of Louis XIV, the king of France. The gallery grew until it was longer than Versailles’s Hall of Mirrors, but apparently size didn’t matter: Marie disguised herself as a man and ran off to France. There have been more recent intrigues, but they have operated at a lower aristocratic altitude.

Oddone Colonna, the namesake of an ancestor who was pope, recently failed to persuade an Italian court that his American stepmother—a former beauty pageant winner and reported girlfriend of Bob Hope and Bing Crosby—was already married when she wed his late father and so should be blocked from her inheritance.

When I ask Don Prospero about the matter, he draws a blank. “Ah yes, these are the cousins,” he says suddenly, adding that they live nearby. “We call it the Little Colonna Palace.” The main attraction, in other words, is his place. But the soft-spoken prince is as humble about his property as the head of one of Rome’s great families can reasonably be.

“Roman homes are for receiving people,” Don Prospero says, clad in an elegant navy suit; he calls himself the “custodian pro tempore” of a 700-year home renovation. He says he wants the aficionados who buy tickets on Saturdays, or the ones who make reservations for special pilgrimages during the week, to feel the same embrace his ancestors extended to fellow nobles. Art historians have had access to the Colonna archives for decades, and a new catalog of the paintings in Princess Isabelle’s apartment was presented in June.

Archivists have begun digitizing the family’s letters, and the palace’s resident curator now oversees an Instagram account (@galleriacolonna) that has amassed more than 10,000 followers. A virtual tour, however, would be a poor substitute for the real thing, which hides in plain sight, camouflaged behind a grimy façade and a hokey wax museum storefront.

Although Rome is experiencing another sad decline outside these walls, and centuries of economic erosion have taken their toll on the city’s nobility and their once-gleaming palazzi, Palazzo Colonna is in remarkable shape. It is a sparkling, verdant estate of 15 acres filled with what art historian and Colonna family expert Letizia Cenci calls a palimpsest of Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, and Roman Rococo styles.

In one room a pink granite crocodile salvaged from the ancient Roman Temple of Serapis and a veiled bust of the emperor Augustus share the space with Renaissance frescoes and a rare 17th-century painted night clock.

Petrarch walked the grounds, and Michelangelo exchanged letters with a 16th-century ancestor of Don Prospero’s, the poet Vittoria Colonna, whose face the master incorporated into The Last Judgment. Bernini was a frequent guest and may have offered opinions about the design of the gallery, which was finally finished in 1703. Caravaggio planned his escape to Naples here after he killed a man.

More recently Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn shot the final scene of Roman Holiday in the gallery, the frescoes of which later served as the firmament for Donatella Versace and Anna Wintour when they introduced the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Heavenly Bodies” exhibit to the press; Italian fashion labels, from Gucci to Max Mara, invite guests to the palazzo for tours.

In March, Peng Liyuan, the first lady of China and a former diva and fashion plate in her own right, received a private tour of the gallery from Don Prospero and his wife during President Xi Jinping’s state visit to Italy.

The density of the collection is dizzying. In one room so many vivid skies and oceans by Caspar van Wittel are hung that the chamber seems to be floating in the clouds. Another room is so solidly covered in landscapes that I nearly missed the masterpiece painted on copper by Jan Brueghel the Elder.

Upstairs, the palace’s most renowned work, The Bean-Eater by Annibale Carracci (which is especially famous in Italy thanks to its presence on the cover of a popular cookbook, The Talisman of Happiness), hangs below Don Prospero’s favorite painting, Bronzino’s picture of the madonna protecting the sleeping baby Jesus from a mischievous baby John the Baptist.

Through it all, through the clashing contrasts and the shock of color, one decorative motif stands out: the colonna, Italian for column. “There are columns everywhere!” Don Prospero says, as the buses outside rattle the windows of the gallery. “You can’t forget for even a minute where you are. Wherever you look—look at the frescoes, look under the console, look here, look up there—a column. Even in the center of the courtyard.”

Since 1252, more than 30 generations of the family have resided at more or less the same address on Piazza Santi Apostoli, between the present-day Piazza Venezia and the Quirinal hill.

Starting in the brutal Middle Ages as a fortress to repulse attacks by the rival Orsini family, the palace grew slowly. By 1420 it was the seat of the papacy for Martin V—aka Oddone Colonna or, as Don Prospero casually calls him, “a pope from the family.” Along the way the Colonnas became members of Rome’s so-called Black Nobility, aristocrats who derived their titles and privileges from the pope and not mere socialites.

The current pontiff, Pope Francis, is facing his own insurrection by traditionalists, some of whom these days prefer the palace of Princess Gloria von Thurn und Taxis. Francis, whom Don Prospero has served as a lay attendant with the rank Gentleman of His Holiness, is, to put it mildly, less interested than his predecessors in Rome’s white-gloved nobles. But Don Prospero refuses to utter a critical syllable. “You never challenge the pope,” he says.

Don Prospero lives here in the personal residence, which is off-limits to the public, with his wife Jeanne, with whom he has two adult children, and their shih tzu Punto (Italian for period). (Another shih tzu, named Virgola, Italian for comma, died recently.) Don Prospero’s sister and brother live here as well, although their eldest sibling, Prince Marcantonio, who sparked some gossip years ago by marrying a commoner, does not reside in the palace. (“That was his choice,” Don Prospero says.) Various nieces and their friends have partied in the gallery on their 18th birthdays and been married under its frescoes of Prince Marcantonio II.

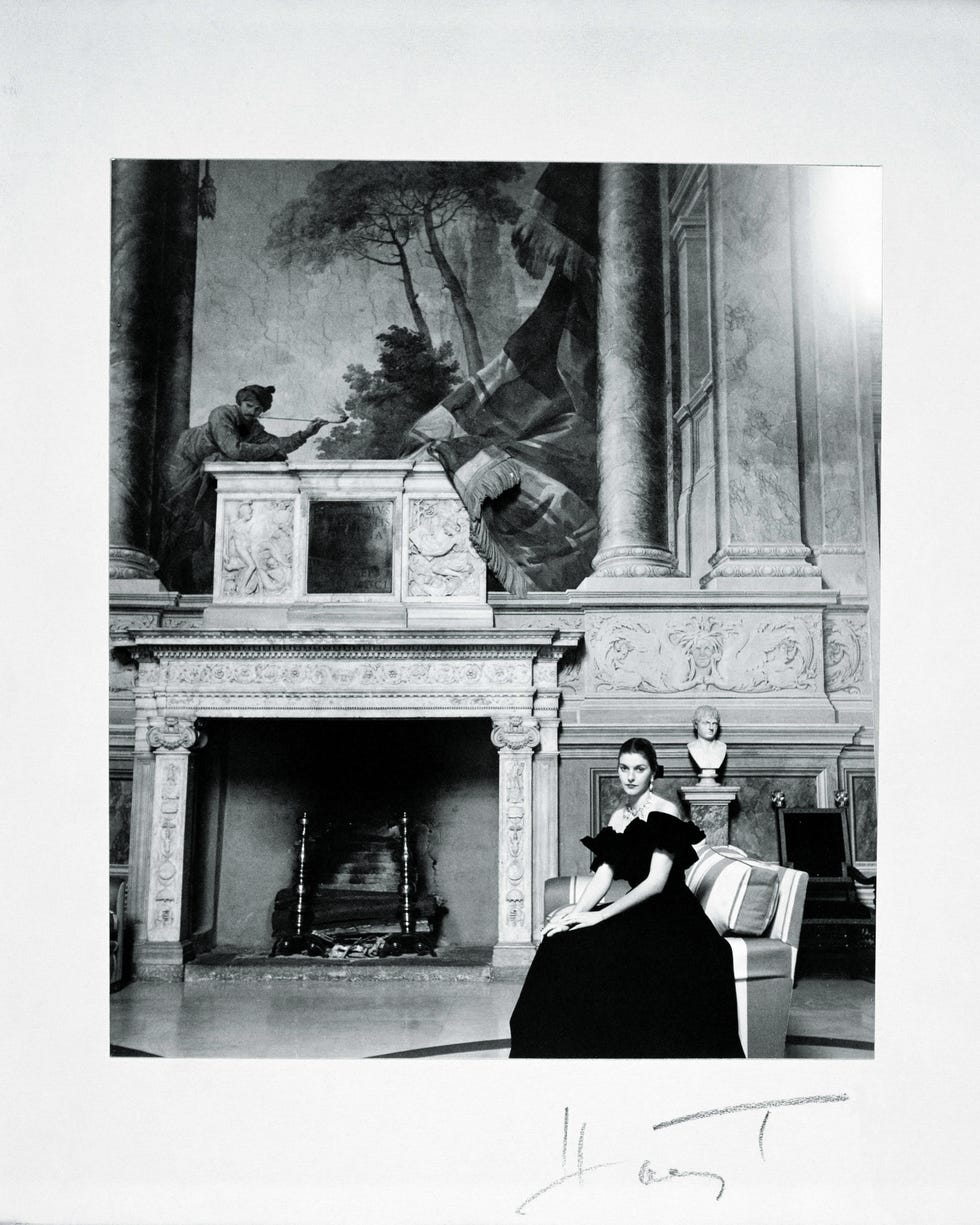

Photos of the family decorate end tables in the Tempesta room in the remarkably well-preserved apartment of Princess Isabelle. And in the nearby ballroom, atop a grand piano, sits a photograph taken circa 1960 by Slim Aarons for this magazine of the glamorous Princess Milagros Colonna posing in the gallery with her son, the four-year-old Prospero.

He is wearing powder-blue shorts and a shirt with a ruffled neckline, an outfit that was apparently the standard Colonna child uniform. His father Aspreno had a nearly identical outfit and hairdo in a photo taken with his mother, Princess Isabelle, 40 years earlier.

The family photos are meant to evoke coziness (albeit of a kind more noble than Netflix and ice cream) to remind visitors that this is a living, breathing home. It is that care for the family legacy that sets the Colonna palace apart from the other regal estates in the city. Of the great families whose private collections are considered part of the nation’s cultural heritage—meaning they cannot be sold or broken up by the family without government approval—the Colonnas have struck perhaps the best balance between providing access to the public while maintaining an aura of appointment-only exclusivity.

Down the block, for example, the Doria Pamphilj Gallery is open every day and holds more masterpieces, including wonderful Caravaggios and a world class Velázquez portrait of the Pamphilj pope, Innocent X. But during one winter visit the rooms were so cold they groaned more like a creaky museum (I was actually shivering). The chill may also have been inspired by the scandal the devoutly Catholic Princess Gesine Doria Pamphilj caused when she tried to block the children of her gay brother, Prince Jonathan, who were conceived via surrogacy, from receiving their inheritance—despite the fact that both she and her brother were adopted from a London orphanage.

Across the street from the Colonnas’ grand garden entrance, near the residence of Italy’s president, is the Palazzo Pallavicini-Rospigliosi. Though it features a breathtaking fresco by Guido Reni, it is open only on the first day of the month. Still, that’s better than the Torlonia family’s prized collection of ancient statues, which has apparently been stashed in three large warehouses while the litigious heirs bicker.

Intrigue is of course inevitable in any family as old as this one. And Palazzo Colonna is as rife with stories as it is with gilt work and trompe l’oeil. Don Prospero, stepping off the bridge that connects the garden to the gallery, seems to walk in the footsteps of the wise predecessors who protected the palace when Rome was sacked in 1527. Every day he checks that the flowers are fresh, that the lights are bright, and that nothing distracts from his family’s treasures. He says he has simply sought to preserve, as in any house, “the atmosphere of a home.”

Maybe not any old house, I offer. “No,” he leans back to chuckle again. “Not any house.”

To make a reservation, E-mail info@galleriacolonna.it.

This story appears in the October 2019 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

Jason Horowitz is the Rome bureau chief of The Times, covering Italy, the Vatican, Greece and other parts of Southern Europe.