The Mortifications of Beverly Cleary

The author recognized that humiliation is a kind of trauma—and that gentle humor could help neutralize it.

The childhood memories we retain most searingly tend to involve shame. When I was 6, after being chided twice for talking too loudly during lunch, I was made to stand in the cafeteria by myself until the other kids finished their food. I can’t even type that sentence without flushing at how conspicuously bad I felt, and how alone. Humiliation is a kind of trauma; when we experience it, our nervous system floods us with adrenaline, heightening our perception and preserving the memory as a warning against future social transgression. And childhood is nothing if not a series of bungles, one maladroit, painfully public flop after another.

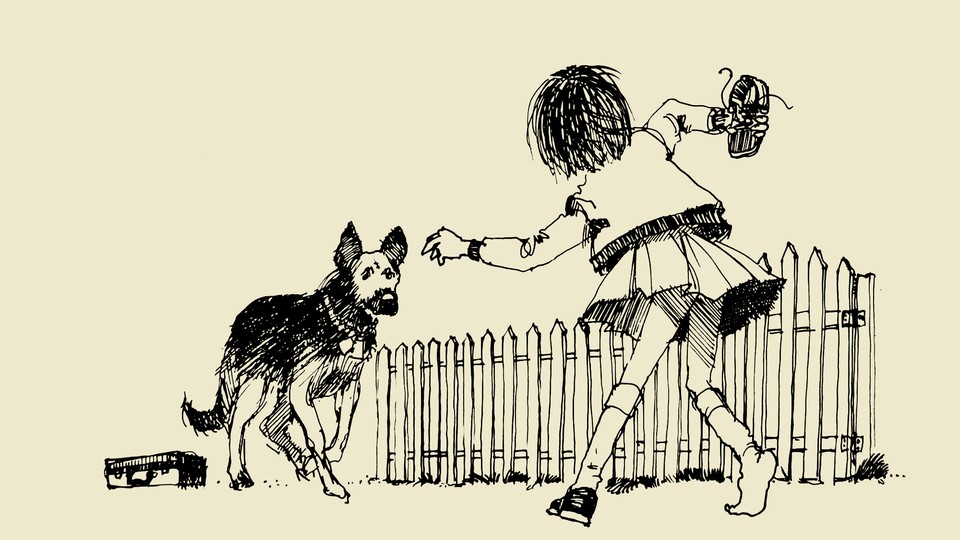

Nobody understood this better than Beverly Cleary. The children’s author, who died last week at the splendid age of 104, has been heralded for the way she captured—sweetly, and with humor—all the ordinary ups and downs of childhood: sibling rivalry, misunderstandings, having a teacher who you can sense doesn’t like you. But for me, and I’d posit for millions of other kids who messed up everything all the time, the awkwardness of Cleary’s characters was everything. My memories of them are defined by their humiliations. There’s Ellen Tebbits trying, with ungainly persistence, to pull an enormous beet out of the ground to bring to class, tearing her dress, covering herself in mud, and having to be rescued by her friend’s older brother. And Ramona Quimby, after being frightened by a dog and throwing her shoe at him, finding herself one shoe short at school on the day she finally gets picked to lead the flag salute. And Ramona’s equable big sister, Beezus, left weeping after a misadventure at a local beauty school leaves her with, horror of horrors, “forty-year-old hair.”

As recounted in Cleary’s first memoir, 1988’s A Girl From Yamhill, the author’s earliest memory was defined by calamity: Cleary, 2 years old and living on her parents’ Oregon farm, is running by her mother’s side when she falls, tearing holes in her brown cotton stockings and skinning her knees. Her mother tells her never, ever to forget the day. Cleary dutifully remembers the stumble and the ruined stockings, but not the context—later, her mother explains that the day marked the end of the First World War. In an essay for The Horn Book Magazine, Cleary described her family’s move to Portland, where she found herself, at age 6, “confined to a city classroom full of strange children after a life of freedom and isolation on a farm.” Even worse was that her first-grade class had three groups for readers—Bluebirds, Redbirds, and Blackbirds—and Cleary found herself assigned to the group for children who were struggling. “To be a Blackbird was to be disgraced,” she wrote. “I wanted to read, but somehow I could not. I wept at home while my puzzled mother tried to drill me on the word charts.”

Thinking of a child’s shame as a blessing seems strange, but Cleary’s early struggles with letters left her with two powerful assets. One was a spider-sense for the fierce jolt and slow burn of childhood mortification—in addition to her own feelings of ineptitude, she remembered how, when a boy lost his place during a reading drill, he was banished to the cloakroom to stew among everyone’s bags and muddy boots. The other was a devoted belief that children would never learn to love reading if the only books they were given were boring. One rainy Sunday afternoon, having efficiently but begrudgingly mastered literacy, Cleary began to read, “out of boredom” and drawn in by its pictures, The Dutch Twins, by Lucy Fitch Perkins. In one chapter, the boy twin, Kit, falls into the Zuider Zee, which Cleary could laugh at “because I had once fallen into the Yamhill River during a church picnic.”

To find something funny is to take away its power. In the more than 40 books Cleary published, what is most striking is how she balances empathy and connection with an ability to neutralize shame with gentle humor. Her first published work, Henry Huggins, was devised while Cleary was working as a children’s librarian in Yakima, Washington, after a boy, unimpressed by the selection of books on offer, asked her where the books about boys like him were. Her second, Ellen Tebbits, is about a third grader beset by humiliations: a boy who won’t stop teasing her, a rift with her best friend over a badly sewn dress, and the secret shame of the woolen underwear her mother makes her wear to dance class. Throughout the lesson, Ellen’s underwear slips past her waist; as she repeatedly tugs it up, her every movement is satirically imitated by Otis, the ballet teacher’s vexing son, until Ellen is almost in tears. She’s saved by Austine, a girl who eventually reveals that she’s wearing similarly awful thermals. I was 7 when I read this book, and I had no idea what woolen underwear was; it didn’t in the least matter. The depth of Ellen’s agony was enough to know how awful it must have been.

The specific mortifications of Cleary’s characters make for great writing, but the accessibility of their feelings is what makes her books timeless. If you’ve never tried to dig an enormous beet out of an abandoned lot to bring to show-and-tell, you’ve surely attempted a grandiose deed to win somebody’s favor that ended in disaster. In Fifteen, one of Cleary’s few books for young adults, the author’s potentially moony portrait of a 1950s teenager who yearns to find love is distinguished by the astuteness of Jane Purdy’s inner monologue. “The trouble with me,” Jane thinks, walking breathlessly up a hill as a couple of her high-school peers drive by, “is that I am not the cashmere sweater type like Marcy.” Marcy wears her gorgeous clothes indifferently and dates the most popular boys in school; Jane has one cashmere sweater, which she takes off the minute she gets home from school to preserve it, and has only ever dated “a family friend named George, who was an inch shorter than she was and carried his money in a change purse instead of loose in his pocket and took her straight home from the movies.” (Cashmere and change purses, it turns out, are timeless motifs of human phenotypes.) When Jane finally scores a date with Stan, a sweet boy a year older who delivers pet food, she can’t get her arm through her sleeve when he tries to help her put on her coat.

Throughout Cleary’s writing, she’s resolutely on the side of the awkward Janes, the blundering Ellens, the pesky Ramonas. Ramona Quimby begins her literary life as a thorn in her sister Beezus’s side but later becomes the undisputed queen of Cleary’s fiction. If Beezus is kind, hardworking, and poised, Ramona is messy, scrappy, imaginative, and constantly aggrieved. Her curious impulses and hot temper lead to scrapes, which in turn lead to her inevitable humiliation. In Ramona the Brave, after destroying an artwork made by a student who copied her, Ramona is forced to publicly apologize. She feels “as if she were walking on someone else’s feet. They carried her to the front of the room, even though she did not want them to. There she stood, thinking, I won’t! I won’t! while trapped by twenty-five pairs of eyes … Her cheeks were hot. Her eyes were too dry for tears, and her mouth too dry for words.”

In Cleary’s books, shame is spiky and physiological and profound; it’s also redeemed by grace. Ramona’s humiliating experience with her lost shoe is transformed when her teacher remarks how brave she was. Ellen is forgiven by Austine after accidentally slapping her in a classroom incident sparked by the meddlesome Otis. Jane is forgiven by Stan after she lets his friend kiss her to try to prove how sophisticated she is, and learns that everyone feels awkward and clumsy at times. The mortification that Cleary’s characters suffer is always lessened by the knowledge that they are not so alone: Everyone has their own version of a scary dog, or a giant beet, or a Cashmere Marcy. The gift of reading Cleary’s stories is in figuring that out.