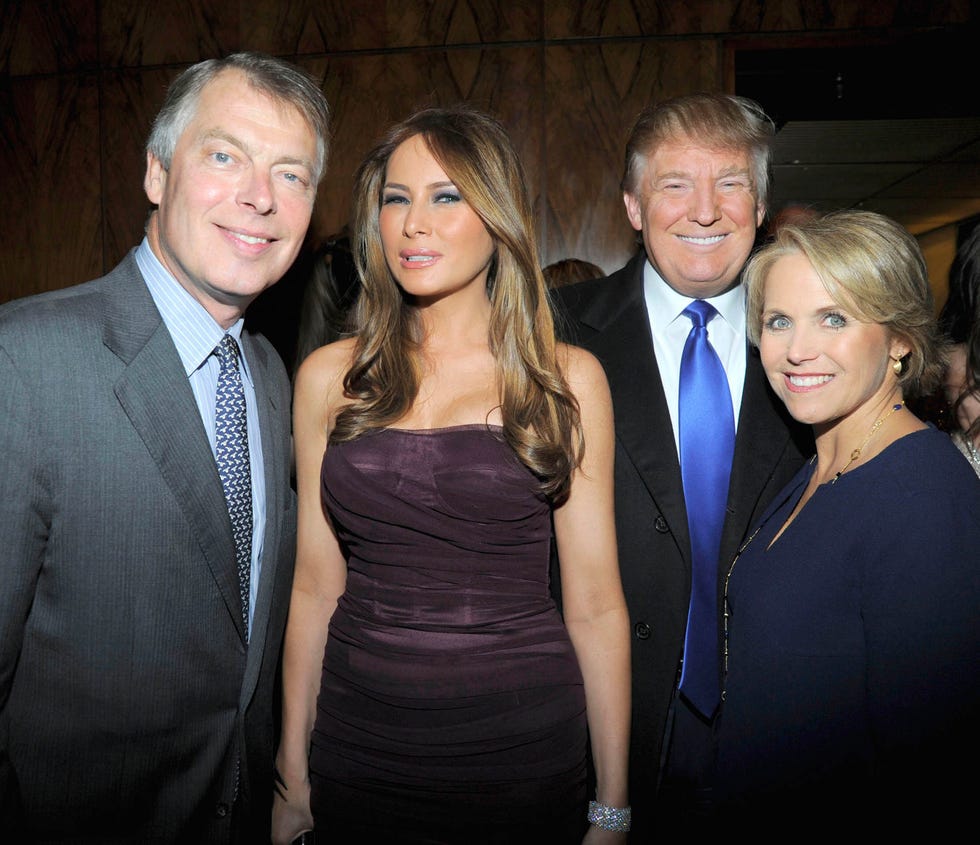

Donald Trump and his wife, Melania, were stationed at the top of the grand staircase in the Four Seasons Grill Room, a longtime gathering place for Manhattan’s power brokers in business and the media. The event had just started, and Trump, then host of The Apprentice, still had his long black coat on over his navy suit. Melania was draped in an airy eggplant-hued cocktail dress.

The party was for veteran Page Six editor Richard Johnson, who had just moved to Los Angeles to work for Rupert Murdoch’s new iPad newspaper, The Daily, and New York’s elite were there to toast him. Katie Couric, Martha Stewart, and Jay McInerney mingled with Page Six reporters as well as publicists like Ken Sunshine, conversation dinning over the funky seventies mixes. Page Six, the gossip column in the New York Post, is an institution built on tipsters, anonymous sources, and old-fashioned reporting. Appearing in it means you aren’t just a success in your line of business; you are a true boldfaced name. You matter. Items about movie stars appear alongside stories about socialites and power players—as long as you make for good copy, the playing field is level. The fear Page Six strikes in its subjects has made it an indispensable tool for Manhattan’s rich and powerful.

For Page Six, Trump had long been the trifecta: boldfaced name, tipster, and anonymous source. Reporters could call his personal assistant, Norma Foerderer, and within minutes he would call back personally. When contributor Jared Paul Stern called him about a story he was working on concerning Trump’s January 2000 breakup with Melania, he told Stern on the record, “It’s bullshit. It’s not correct.” But the item was peppered with supporting quotes from “one friend” of Trump’s and a “source close to Trump.” Stern says those quotes all came from Trump himself—a practice other former gossip columnists have confirmed Trump employed. Trump, disguised as a friend, said about himself, “He doesn’t care. It’s not like he’s married. . . . [Melania] is a great girl, but Donald has to be free for a while. He didn’t want to get hooked. He decided to cool it.”

(A White House official says, “That NY Post story you are referring to is false,” but wouldn’t comment on Trump supplying the anonymous quotes.)

Trump and Johnson were close—the editor attended two of Trump’s weddings and served as a judge for the Miss Universe pageant when Trump owned the franchise. But the column was about to change. The dapper Johnson, who had been there for a quarter of a century, was being replaced by Emily Smith, a five-foot blond Brit. She had become Johnson’s deputy a year earlier after a stint as the U. S. correspondent for The Sun.

At Johnson’s send-off, in November 2010, Smith, in a simple black sheath dress, made her way around the room as guests congratulated her. When she got to the top of the grand staircase, she was introduced to the Trumps.

“Oh, you’re taking over for Richard Johnson,” Trump said. “Big shoes to fill.”

“I know—and I’m from England, too, so I don’t know how I’m going to do it,” Smith said.

Trump responded, “At least you’re good-looking.”

That interaction, that party, that collection of boldfaced names gathered to honor a newspaperman who traded in gossip seem like a gauzy dream. A moment before the collapse of the media business in which Page Six operated. Institutions crumbled. Social-media companies took shape, giving rise to a new breed of celebrity and, worse, influencer, who saw little value in gossip columns. Eventually, the schmoozy, seemingly harmless gossip at the top of the stairs became the president of the United States—impeached, embattled, spoiling for a fight.

But somehow, Page Six—a column in a newspaper that is printed on paper—has managed to grow. Yes, it has a website and a Twitter feed, and there was even a TV show. But mostly, it’s still something you flip to rather than something you click on. #MeToo may have caused it to check its conscience. TMZ may have made it work harder. Social media may have given celebrities more power to control the news, taking some of the wind out of Page Six’s guess-what-we-just-saw urgency. And yet to the people who run the world, or certain parts of it, Page Six still matters.

How did something built upon a flimsy foundation of celebrity sightings and overheard chitchat become an indestructible mainstay of news and entertainment? So strong it can keep winning a game in which backstabbing, horse-trading, secrets, lies, manipulation, and the occasional fistfight are pretty much part of the rules?

How does Page Six still thrive?

How does Page Six still exist?

When I moved to New York from Florida in 2007 for a job as an associate editor at the New York Post, I’d never heard of Page Six. It quickly became my cheat sheet for how to be a real New Yorker. Page Six had its own language and cast of characters that made it feel like the most exclusive and exciting version of the city. Every morning, I’d grab the paper, turn right to Page Six, and be transported to a world where finance “honchos” I’d never heard of were suddenly intriguing, celebrities I did care about were “canoodling” with one another, and those who mattered were “spotted” at Elaine’s, Le Cirque, or Nello, restaurants I knew only by name and that in my mind were constantly filled with famous people swapping air kisses and dirt.

At the paper, the small Page Six team seemed elusive. They kept to themselves, stationed in the back corner of the newsroom, buried behind stacks of newsprint and books. Although the dress code for tabloid reporters consists mostly of jeans and crumpled dress shirts, I’d see Johnson, always in his crisp suits and perfect flaxen coif, walking silently, regally around the office. His deputy, Paula Froelich, sometimes napped on a couch in the photo editor’s office, near my desk. “Dude, I was exhausted,” Froelich says. “I used to get in at 9:30, 10:00 in the morning. I would leave around 8:00 or 8:30 and then immediately go out, sometimes not getting back home until 3:00, and then six hours later do it again.”

This article appears in the March 2020 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

Tara Palmeri, who was at Page Six from 2010 to 2012, says, “You stay up all night because everyone says that everything goes down after hours, right? Everyone says that the end of the night is when you see people acting up, and that’s when the real drama happens.”

They were filling two pages a day with a dozen or more “items,” the small news stories that constitute Page Six. The column had grown from a single page because luxury advertisers like Saks Fifth Avenue wanted to be placed across from it—and it usually appeared on page 12 or further back.

When Murdoch and then Post editor James Brady launched Page Six on January 3, 1977, it was indeed the sixth page of the paper and the first gossip column to operate as a section—not attached to a single columnist, like those written by legendary gossips Walter Winchell and Hedda Hopper.

The mandate was to cover “the corridors of power.” Competitors came and went, but the 1990s and early 2000s brought a gossip gold rush. One former Page Six staffer says of those days, “When you were at Page Six, the club owners would meet you at the door and hand you an eight ball—it was insane.”

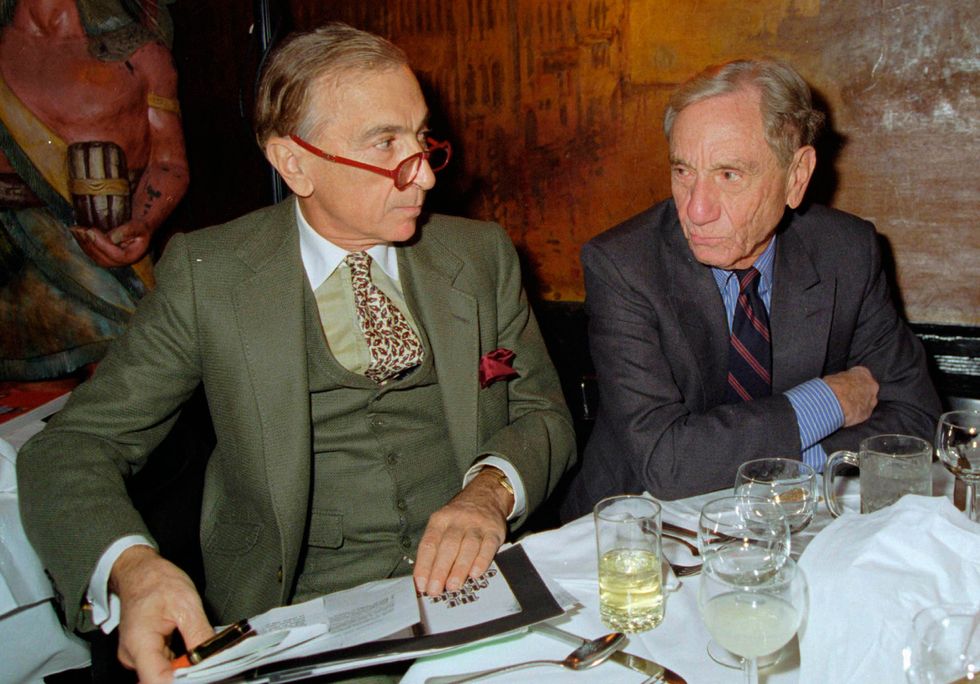

In addition to Page Six, there was Rush & Molloy (a husband-and-wife duo of former Page Six staffers), which launched at the Daily News in 1995. New York magazine had Intelligencer. Esquire (until 1997) and The New York Times had gossip columns. But in a 1994 New York ranking, Page Six topped everyone: “Page Six rests easy at the top of the gossip pile; in terms of performance, prestige and influence, it’s New York’s consensus No. 1 column. And the bitchiest.”

Page Six itself—the actual newspaper column—looks almost exactly as it always has. There’s still a story that stretches across the top of the page: “the lede.” There’s still a two-column-wide item at the bottom right: “the double.” The fonts are the same. Every name is bolded, except those of the dead. There are recurring features like Sightings, which are quick hits revealing where celebrities have been spotted around town; We Hear, events that celebrities are expected to attend; and blind items, pieces of gossip with no name attached, often for legal reasons. (In December, a blind item disclosed that an unnamed A-list actor had been sending dick pics to couples in hopes of interesting them in a threesome.) Reporting methods are mostly the same, too. Page Six has an extensive network of tipsters, sources, verifiers, and helpers. “We rely on our sources more than reporters from other areas of the paper. Often it’s the source that gives rise to the story rather than the event itself,” says Johnson.

In a media environment that prioritizes gaming algorithms to bloat website visits, Page Six reporters still do things the old-fashioned way, spending most nights at events, parties, and dinners cultivating sources, and days working the phones to verify tips. About 24 million people per month read PageSix.com, while 170,000 people read the Post in print and about 200,000 read the Post daily on the app.

Henry Schleiff, group president at the media company Discovery, reads his Post on the treadmill while he watches CNN. “I savor Page Six as my dessert,” he says, marveling at the quality of reporting in the column. “One could argue they’re Woodward and Bernstein on speed.”

For publicists, getting a client in bold can change their trajectory—shine a light on an up-and-comer or help shape the narrative about a celebrity. In the pre-Internet days, each morning, editors at glossy magazines would get a photocopied packet of the day’s gossip, culled by editorial assistants from the New York tabloids and trades and delivered to their desks—fodder that could turn into a bigger story. Today, a Page Six exclusive is often rewritten by dozens of other sites—you’ll find Page Six citations everywhere from Cosmopolitan to The Source to The New Yorker.

“I recently had a conversation with the editor at a magazine, and he was telling me they wait for us to do the story first because they’re scared to do it or they won’t do it,” Page Six executive editor Ian Mohr says. “Then they jump on it as a feature. I see that all the time.”

Page Six reporters have shown an uncanny ability to identify interesting characters, then cover them obsessively until they become first “Page Six famous” and then actual celebrities. New York socialites Paris Hilton and Tinsley Mortimer were Page Six staples—every table dance and club altercation was covered—before they became reality-TV stars. Other times it’s serendipitous. Page Six covered Timothée Chalamet in 2013, when he was a teenager dating Madonna’s daughter Lourdes Leon at Manhattan’s LaGuardia High School who’d had a bit part on Homeland.

And yet getting a call from Page Six will send a chill down a publicist’s spine. “It’s usually a no-number—so it’s a private number—and I panic,” says publicist Kelly Brady, who represents clients including Mortimer and Patti Stanger. “I’m always like, Fuck, it’s Page Six. My heart jumps out of my skin, always. I’m like, Oh my God, what did my client do?

When something salacious happens in the city, odds are someone from the Page Six ecosystem saw it or heard about it—and is itching to be the one to get the satisfying thrill of sharing it.

“Okay, you can out me as a gossip! I’m a Page Six helper,” says R. Couri Hay, an owner of a public-relations firm who has been working with the column since its inception. He says he was the one who gave Page Six one of its most famous blind items ever, about Woody Allen dating Soon-Yi Previn in the early 1990s, after hearing it from Mia Farrow’s mother, Maureen O’Sullivan. (Former Page Six editor Joanna Molloy has told a different story.) “The reality is, I love to gossip. I was born to gossip! I hear a lot. I have information every single day. Call me an adrenaline seeker—I guess some people feel like this when they skydive.” Hay goes to two or three parties a night, five or six nights a week, and calls his Page Six contacts almost daily. Before he even brushes his teeth, Hay grabs his Post to see if one of his items made the cut. “Just today, I woke up and found a couple,” he says. The ultimate rush comes when he gets “the wood”—tabloid-speak for the front page of the paper, where Hay’s items have landed a few times (according to him).

Hay isn’t paid for his tips—Page Six doesn’t pay sources. However, his gossip prowess is useful in his PR business. “Over the years, I’ve been a partner with different nightclubs,” he says. “I remember Kim Kardashian wouldn’t get out of the car—I guess I can tell this story now; it’s ten, fifteen years later—unless you gave her a paper bag with $5,000 in it. The reason I did that is I knew it would end up in Page Six or one of the other gossip columns.” (A rep for Kim Kardashian West says, “Kim actually doesn’t remember this at all.”)

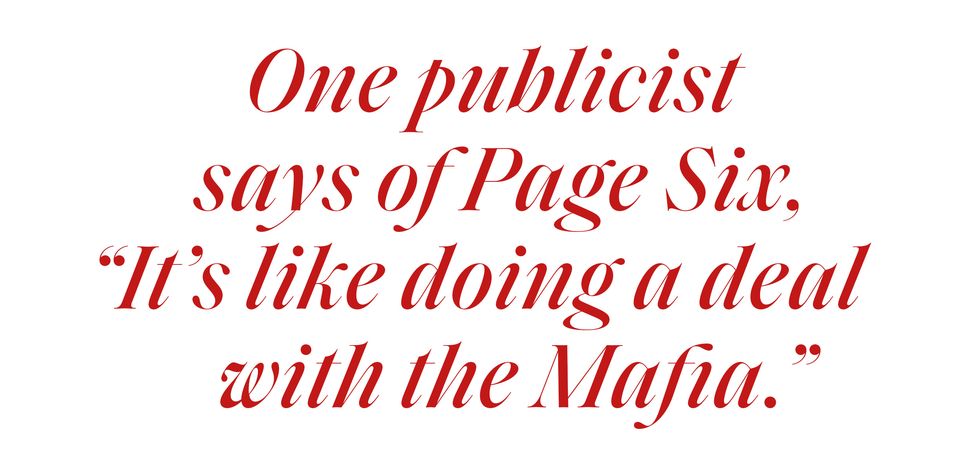

An often unspoken tactic of gossip reporters is the trade: The column will mention a publicist’s client—a restaurant, for example—in exchange for other, more valuable gossip.

“It’s like doing a deal with the Mafia. They’ll lend you a dollar if you pay them back four,” says publicist Kelly Cutrone. “I made a rule with myself about gossip, that I didn’t place gossip that I didn’t know to be true or that could ruin somebody’s life and family.”

In addition to the tipsters, another class of valuable source is the unbiased verifier.

“My role has been of a verifier,” says ubiquitous society photographer Patrick McMullan, who says he never calls in tips himself but has been a reliable ally because he’s so often at parties and events with the boldfaced. “Like somebody would say, ‘You were in the room. Was Charlize Theron there?’ I would say, ‘Yes, she was.’ I guess maybe because I didn’t have a horse in the race, I was a very good person to get the truth from.”

The host of Bravo’s Watch What Happens Live, Andy Cohen, reads Page Six on the Post app, which can assuage his ego when he’s the one being written about. “The great thing [about the app] is when they put something up about me that I don’t like, I know that it’s going to scroll down as the day goes on,” says Cohen.

When the item appears in print, somehow the sting can be worse.

“One time, Kim Cattrall told me that I should get a respectable job, that I should work at Roybers. Like, R-O-Y-B-E-R-S,” says Palmeri. “She meant Reuters.”

There was the time Joss Sackler texted reporter Oli Coleman nothing but a middle-finger emoji after the column’s coverage of her New York Fashion Week show.

Another Page Six reporter says, “Puff Daddy’s publicist called me in tears because she heard I was doing a spread about how he was afraid of clowns and supposedly suffered from this thing called coulrophobia. I was like, I can’t not do this. I don’t care if it ruins the relationship.” (“We remember this to be one of the more laughable calls we received daily from Page Six, who were obsessed with Diddy,” says a member of the artist’s former press team.)

On a dreary afternoon this past December, Smith has just come from the Post’s daily 2:30 pitch meeting. The editor in chief, Stephen Lynch, listens as an editor from each section presents the day’s list-lines—summaries of stories their reporters are chasing. On this particular afternoon, Page Six is working on a tasty lede about NFL Network correspondent Jane Slater finding out an ex had been cheating thanks to his Fitbit showing a bump in his heart rate at 4:00 a.m.

The race-car-red walls of the newsroom, on the tenth floor of the News Corp. building in midtown Manhattan, enclose stark white clusters of desks. CNN, CBS, and Fox News play soundlessly on TVs lining the perimeter. Smith usually sits at a small desk among her reporters, but she leads me to a conference room on the corner of the floor. She rarely sits for interviews. “Oh, it’s deeply uncomfortable! Because the star is Page Six; it’s not me,” she says, shaking her head.

In her early days at Page Six, it wasn’t unusual for Smith to go from an all-night event she was covering straight to the office at 6:00 or 7:00 a.m. “I went to everything and I stayed out all night and just made a point to meet everyone. That was before I became a mother,” says Smith, who has a four-year-old. “It really hasn’t changed. I still go out quite a lot. It’s getting in earlier and not staying out and thinking, Oh, let’s go on to a nightclub and Let’s go to a karaoke bar, or Let’s go back to someone’s house.”

The room we’re sitting in used to be Johnson’s office. “I had to clear the whole thing out, and there were old faxes from Donald Trump in there,” Smith says. Trump would famously fax angry letters to anyone he feuded with—Jerry Seinfeld, Rosie O’Donnell—and simultaneously fax over a copy to Page Six. “I kept some of them, but I wish I’d kept all of them.”

The afternoon I visited the Post offices, Murdoch made his way through the newsroom alone with his head down, transfixed by his phone. He wore a navy suit with a crisp open-collared white dress shirt and bright-blue sneakers that appeared to be the trendy brand Allbirds.

Smith raised a finger his way and said, “Hey, the boss!”

Page Six may not be thought of as a sober journalistic enterprise, but its reporters have broken significant stories over the past forty-three years, and Smith sprinkles the conversation with bombshells she and her team have unearthed. Page Six was the first to report Joe Biden’s son Hunter having a romantic relationship with his brother Beau’s widow. It was there when Trump staffers Hope Hicks and Corey Lewandowski got into a public screaming match, an early sign of chaos within the administration.

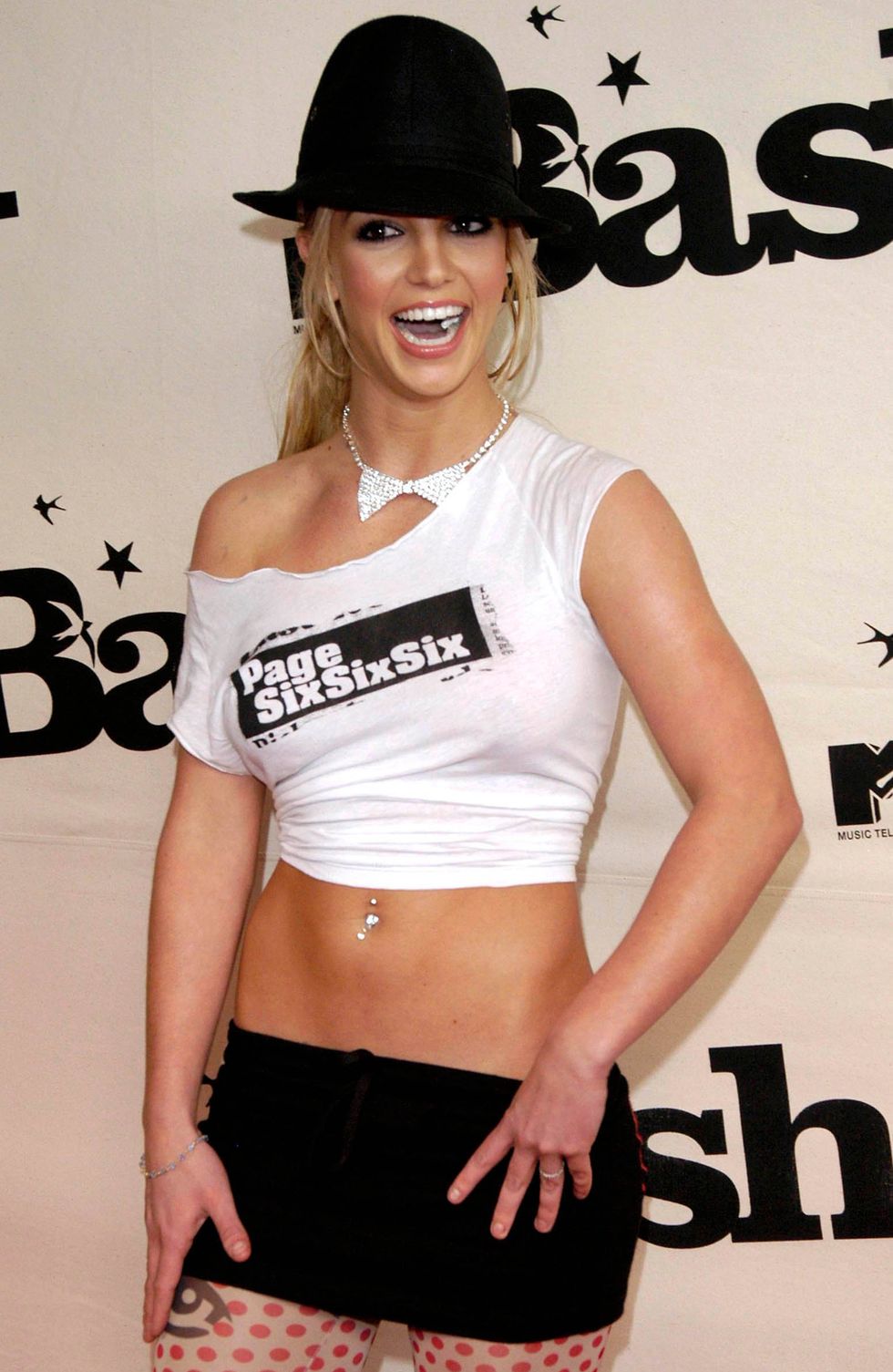

In the early 2000s, the Internet became an increasingly threatening source of competition. In 2004, a blogger named Perez Hilton launched a site called PageSixSixSix.com—a name he had to change after the Post sued him. Gawker .com started in 2002 with its own snarky style of gossip—poking fun, sometimes viciously, at the media establishment, including Page Six.

The differentiator? Reporting. Page Six had more experience at it.

“Gawker was pretty much nothing compared to Page Six. Page Six broke news every day and night and worked their butts off, while Gawker was busy doing their hair or something,” says former Gawker editor Choire Sicha, who now runs the New York Times Styles desk. “Page Six knew the answer to gossip blind items that we didn’t even know enough to ask. There was some sort of enemyship and friendship relationship between Gawker and Page Six over the years, but Page Six was always the big dog. Sometimes the big, bad dog. Of course, Page Six was at times as corrupt as any media outfit could possibly be. It did very reprehensibly bad things over the years. But it also had an honor and a panache that I’ll always admire.”

In 2006, there was an explosive allegation of corruption against Page Six. Stern was accused of extortion involving billionaire supermarket magnate Ron Burkle—demanding money to keep negative information about him out of the column. “We know how to destroy people,” Stern reportedly told Burkle. “It’s what we do. We do it without creating liability. That’s our specialty.” (After a federal investigation, no charges were brought.)

When Johnson ran Page Six, he had the benefit of the last word in his many feuds over the years with the likes of Mickey Rourke (he challenged the actor to a fight), Alec Baldwin (who was dubbed the Bloviator), and Paul Newman (Johnson accused him of lying about his height). Today, Page Six subjects can say their piece on Twitter as soon as the paper hits the newsstand.

Social media is one of the starkest differences between Johnson’s era and Smith’s. Celebrities can use social media to try to beat gossip columns at their own game, negating scoops by announcing their engagements, divorces, and pregnancies on their Instagram pages—on their terms. There are gossip Instagram accounts like the wildly popular Shade Room, private gossip Facebook groups, secret invite-only gossip newsletters, and fan Twitter accounts that follow the every move of stars like Beyoncé and Taylor Swift—all new competition for Page Six.

On March 14, 2018, Smith broke the news that Donald Trump Jr. and his wife, Vanessa, were splitting up, and the fiery, short-lived White House communications director Anthony Scaramucci tweeted that Smith was “a person with no morals or journalistic standards. Living off of others people’s pain. Beware! She will stop at nothing to hurt innocents. Especially your children.”

(Smith was eventually proved right—the Trumps split, and Don Jr. is dating former Fox News host Kimberly Guilfoyle.)

At the mention of this, Smith seems to sit up a little taller. “I welcome the feedback,” she says. “You get people who don’t like stories, and they’ll go at you. But that’s part of the fun. That’s part of the game. If we are dishing it out in a gossip column, you have to expect to get it back.”

There have been tipsters, there have been sources, there have been mutually beneficial relationships. And then there was Harvey Weinstein.

For more than two decades, two New York power brokers—Page Six and Weinstein himself—used each other masterfully. One would occasionally take the other down, but year in and year out, Page Six sucked information from Weinstein and Weinstein sucked positive coverage from Page Six. And when the subject of this coverage was movie premieres or after-parties or even the occasional instance of bad behavior, there was no harm done. But what happens when one of your best sources turns out to be an alleged rapist and the catalyst for the entire #MeToo movement?

Weinstein has been more extensively covered in Page Six than just about anyone else—more than eleven thousand times, according to his lawyers. They tried to use this as an excuse to have his trial moved last year, describing the coverage as “biased and sensational.” But a closer look shows that Weinstein’s aggressive attempts to shape Page Six coverage go back many years.

In 2000, Froelich was covering a book party at the trendy downtown hotel the Tribeca Grand, hosted by Weinstein. When Rebecca Traister, a reporter for the elite, brainy Manhattan newspaper The New York Observer, asked Weinstein a question he didn’t like, he called her a cunt, and her colleague Andrew Goldman stepped in.

Weinstein grabbed Goldman, put him into a headlock, and dragged him out onto the sidewalk, screaming, “You know what? I’m the fucking sheriff of this fucking lawless piece-of-shit town.”

“I go in the next day and I’m like, ‘I’m gonna write [about] it,’ ” Froelich says. “Richard didn’t want to run it. And then I said, ‘If you don’t run it, I quit.’ ”

Weinstein’s publicists told Froelich that the other reporters at the event had agreed not to write about the incident, she recalls. Goldman says Froelich called him that afternoon saying she was concerned about how Weinstein’s publicists were spinning the incident, so Goldman decided to file a police report.

The item that ran in Page Six, which Froelich says was “heavily edited,” begins, “A couple of pushy reporters for the New York Observer pushed Miramax chief Harvey Weinstein to the breaking point, causing an ugly scene at what should have been a joyous celebration for former MTV veejay Karen Duffy.”

Today, Johnson says Weinstein’s reps denied the attack—and quickly points to the New York Times coverage of the night, which, like the Page Six item, cast Goldman and Traister as the aggressors and Weinstein as the innocent victim trying to be civil. When read back the beginning of the Page Six story, Johnson pauses for a beat. “Oh,” he says. “Well, that was probably Harvey’s work. It sounds to me like the reporters were the victims here, not the perpetrators.”

When asked if he has any regrets about how Page Six covered Weinstein, Johnson says, “Looking back, I wish I’d attacked him as a pervert from the very beginning, but, you know, I didn’t realize it. He was the leading independent filmmaker in New York for many years.”

Weinstein controlled who got access to his parties, premieres, and stars. “He was another person who just implicitly understood how if you give, you get,” says George Rush, who was at Page Six in the late eighties and early nineties. “While studio publicists would keep a gossip columnist as far away as possible from the star at a premiere, Harvey would corral the star and pull her to the gossip columnist and say, ‘George is a good guy; we trust him. Take care of her. Be nice, George.’ And so everybody would win. You’d have your exclusive interview with Winona Ryder, Gwyneth Paltrow, Brad Pitt. These people were coming up—they were babies.”

Weinstein would oscillate from charming and complimentary to threatening and bullying and back to get his way. But Rush and other former gossip columnists say they never heard stories of Weinstein being sexually abusive—allegations first reported in 2017 by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey in The New York Times and by Ronan Farrow in The New Yorker. Froelich, however, says she’d heard rumors about Weinstein and Rose McGowan, who later publicly accused Weinstein of raping her.

“There were often rumors about Rose because Rose would talk about it sometimes,” Froelich says. “If people aren’t gonna go on the record, you can’t do it. You know, it’s not like I had somebody leaking me the inside papers from Miramax or from the Weinstein Company that show all the documentation of it.”

Miramax bought the rights to Froelich’s book at auction while she was still at the Post, though she says that never affected her reporting on Weinstein. She says, “He would tell people, ‘I bought that book!’ And I was like, ‘Whatever, dude, I don’t give a shit.’ ”

In 2015, the Post reported on Ambra Battilana Gutierrez’s harassment accusations against Weinstein in front-page stories accompanied by images of the model in lingerie—and they ran online on PageSix.com. Stories by news reporters sometimes run under the Page Six banner on the website, but in those cases it’s Page Six that gets the credit when they’re cited by other publications. One story quoted an anonymous source calling the case extortion. The source accused the model of taking Broadway tickets and asking for a film role after the molestation claim.

Battilana Gutierrez did take the tickets—attending the play at the encouragement of the police and wearing a wire, she said on Farrow’s Catch and Kill podcast. It was after that play, outside Weinstein’s hotel room, with several cops stationed around the hotel, that she recorded Weinstein admitting he’d groped her.

Weinstein has since been accused by more than eighty women of sexual harassment and assault, up to and including rape. (Weinstein has denied all allegations of “nonconsensual sex.”) In 2017, Battilana Gutierrez spoke to a Post reporter about how painful the 2015 tabloid coverage had been for her. “A friend texted me a photo of the [Post] cover and asked me what was happening,” she said. “I didn’t have the power to defend myself. . . . It really broke my heart.”

In that story, the Post concedes that when it came to the 2015 coverage of Battilana Gutierrez, “Weinstein called the Post with his account” of her asking for a film role—but the sources quoted in that piece were unnamed, and it wasn’t made clear that Weinstein was one of them.

Though Smith has one of four bylines on the Broadway-tickets story, she says the coverage wasn’t led by Page Six but rather by the news team at the Post, and that she didn’t edit the stories or control the tone in which they were written.

Weinstein continued to turn to Page Six after the horrifying allegations were revealed in 2017. He did a series of interviews with Smith in which he talked about being “profoundly devastated” about his wife leaving him, saying he “bears responsibility” for his behavior, while at the same time criticizing The New York Times for “reckless reporting.”

This past December, Coleman wrote a snarky item about Weinstein’s seemingly selective use of a walker, implying it may have been used to garner sympathy before his January trial for predatory sexual assault and rape. And once again, Weinstein went to the Post—this time for a bizarre interview that ran on PageSix.com. Sitting in a private hospital suite, he refused to talk about the allegations against him but “whined” that he should be remembered more for things like hiring female directors than for the “sickening accusations.”

Though the short-lived Page Six TV series reported in October 2017 that Weinstein was calling Smith from rehab nearly nightly, Smith says she’s no longer in contact with him.

It’s difficult to read Page Six without thinking about how men like Weinstein used it as a tool for so many years—how it contributed to his fame at the expense of the reputations of women like Battilana Gutierrez.

The ways in which Page Six skirts the norms of traditional journalism—blind items, trades, frequent anonymous sources—cultivate its mystery and allure. But they also make it difficult to discern clear motives and create a fog behind which nefarious players can operate. The editors of Page Six help decide who is famous and who is infamous. We, the readers, will never know who planted that salacious item about a starlet canoodling; we just have to believe that the person writing it knows—and cares about—the motivation. On the surface, Page Six has started to evolve: Gone are the cruel nicknames like “portly pepperpot,” “aging pop tart,” and “celebutard.” “I try not to be mean anymore,” Smith says. “I wouldn’t call Monica Lewinsky a portly pepperpot anymore. And she’s told me many times how she really didn’t like that.”

Page Six is becoming more global as well, to appeal to its digital audience. (The downside: Reading it, particularly online, feels less like sneaking into an exclusive party and more like reading any number of gossip sites.)

Still, in spite of its history—or, more likely, because of it—Page Six has persevered.

“When I think of a Park Avenue building, from the guy answering the door in the package room to the guy in the penthouse—they’re all avid Page Six readers,” says Mohr.

Elaine’s, a late-night restaurant on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, was a favorite of all kinds of fascinating New York characters until it closed in 2011 after forty-eight years in business. Writers including Nora Ephron, Tom Wolfe, and Joan Didion hung out there. So did movie stars like Judy Garland, Jack Nicholson, and, famously, Woody Allen, all of which made it a backdrop to countless Page Six items. When Johnson ran the column, he’d often finish his evenings by stopping into Elaine’s and sitting at the large center table where owner Elaine Kaufman—herself a fascinating New York character—held court, to see if she’d seen anything interesting that night.

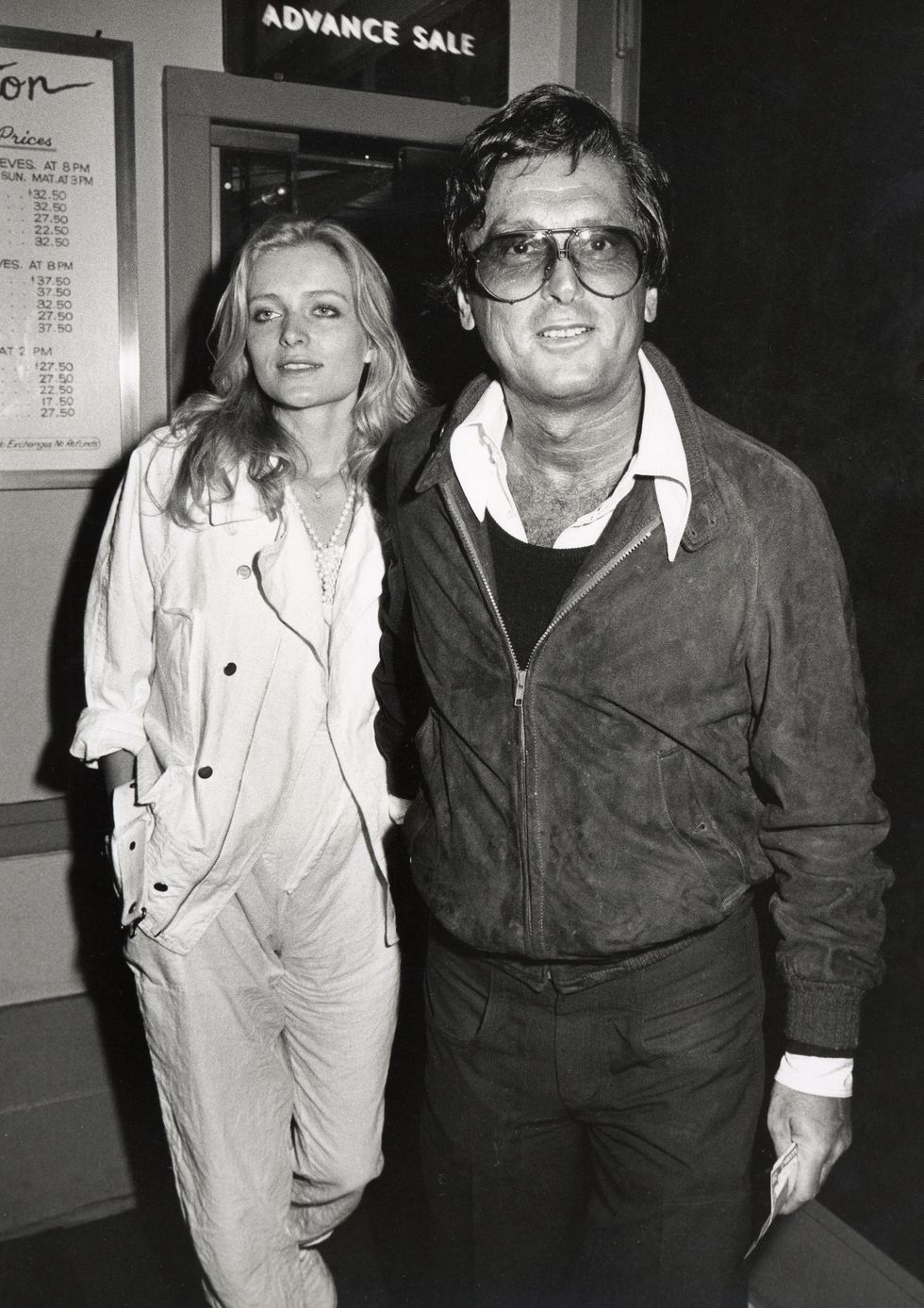

Brian McDonald, who worked at Elaine’s from 1986 to 1999 as a bartender and manager, was a reliable Page Six tipster. Like the time around thirty years ago when Chinatown producer and Hollywood roustabout Robert Evans strolled into the dim, storied dining room around midnight.

“He says the words that put a chill through the heart of every regular customer: ‘I just had dinner at Le Cirque. I’m here for coffee and dessert,’ ” McDonald says, pausing for dramatic effect. “Elaine said, ‘If you had dinner at Le Cirque, you should have stuck around and had dessert there, too,’ and walked away. So he sat at a table—he was there with two stunning women, blond-haired women—and he ordered dinner for everybody, and it sat there, uneaten, just to make Elaine happy.”

McDonald smiles.

“I called that item in.”

The Evans tidbit is, in a way, the perfect Page Six item. Evans was a big name, a mysterious creature whom most people had no access to, never saw. Elaine’s was an institution, the kind of place most people might visit in hopes of catching a glimpse of someone like Robert Evans but never do. The item captured Kaufman’s gruff charm and Evans’s showbiz ego. What actually happened? Not much. The exchange was utterly meaningless. And that delicious meaninglessness is one big reason so many people have loved the column so much for so long. It’s about these titillating and amusing and sometimes shocking things happening around us all the time, late at night or at exclusive lunch spots or in the lobbies of luxury co-ops—things we would have witnessed if we’d happened to be there.

Alas, we weren’t.

But Page Six was. So for a few minutes as we ride the subway or drink our coffee or wait for the doctor, we get to escape our little lives that no one ever writes about. We get to be there, too.

Kate Storey is the author of White House by the Sea: A Century of the Kennedys at Hyannis Port and the senior features editor at Rolling Stone. She was previously a staff writer at Esquire, where she covered culture and politics, and has written long-form profiles and narrative features for Vanity Fair, Marie Claire, Town & Country, and other publications.