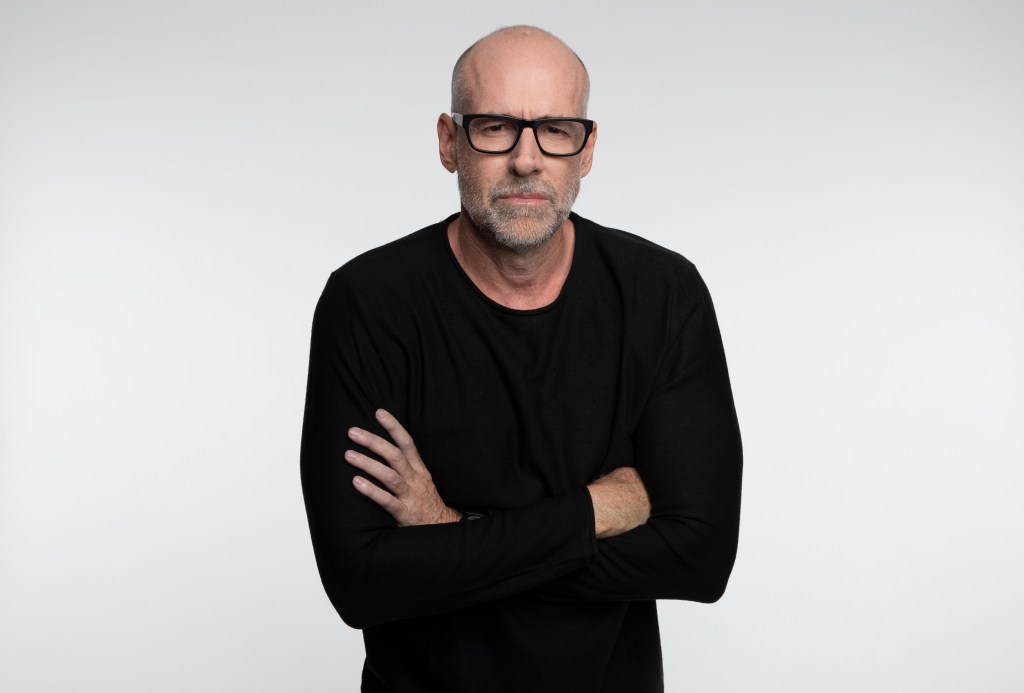

Scott Galloway, the New York University professor, author, and tech entrepreneur, is taking the wraps off a $30 million Series A round for his newest company, Section4, a platform for business “upskilling” that has now raised $37 million altogether.

The company is premised on the belief that millions of workers need help to stay competitive and employable, yet not all have access to, or interest in, costly graduate school programs. In fact, Section4 thinks more affordable “sprints” — or two- to three-long week courses taught by prominent professors from top schools that can also be mind expanding — is the way to go.

Whether that thesis proves out remains to be seen, but Section4 — whose new round was led by General Catalyst, with participation from Learn Capital and GSV Ventures — says early indications are good and that it already has 10,000 alums from dozens of countries.

We talked with Galloway yesterday about who, specifically, Section4 aims to serve, what percentage of its students is outside the U.S., and how universities feel about their professors participating in a startup that could eat into their own revenue. Excerpts from that chat follow, edited lightly for length.

TC: Why start this company?

SG: Graduate education was transformative in my life, and I enjoy teaching, and we thought there was an opportunity — because of the pandemic and changing behaviors — to start an online ed concept that tried to deliver 50% to 70% of the value of an elite MBA elective at 10% of the cost and 1% of the friction.

TC: Is this competition then for shorter executive MBA programs?

SG: I would say not even exec MBAs, because part-time MBAs get a certification that is still incredibly valuable in the marketplace. And we don’t offer that. It’s somewhat competitive [instead] with executive education, the bring-50-people-from-Pfizer-in-for-two-days-and-charge-a-bunch-of-money-and- have-them-eat-lunch-together-on-campus-in-Palo Alto-and-throw-some-professors-at-them-for-some learning. I would argue that we’re competitive with that. It’s incredibly expensive, both financially and just [through] trying to gather 40 or 50 executives.

Also, quite frankly, it’s a little bit exclusionary because a company like Verizon can only send 100 people to Wharton’s exec ed, and we’re hoping that we can run thousands of people from these companies through our programs.

TC: So these are companies that are your customers, not individuals seeking betterment for themselves.

SG: It’s both. The funnel is: organically people sign up. And the idea is that the course costs $700, $800 versus $7,000, which is what it costs to take an elective at an elite business school right now. So for example, 120 people have organically, individually signed up on their own who work at Google. Then our expectation is that over time, these companies will approach us and say, ‘We would like to buy a certain number of seats or a membership that covers 100 or 1,000 of our employees.’

TC: You say Section4 has already taught 10,000 students; when did you start offering your programming?

SG: In March of last year. Our first course had 300 people; the course I just wrapped up had 1,500, so it scales pretty well.

What’s different about it is our completion rates, which are 70%-plus. The curse of online ed is that completion rates are really low because video doesn’t capture people or create an intensity, and we try to be a mix of synchronous and asynchronous, so [there is] project work and teams, live streams with the professor, and live one-on-one sessions with a TA. It’s meant to hold people accountable and engage them.

TC: You’re promising students access to top professors like yourself. How do the schools for which they teach feel about this? They’re perhaps helping build the brand of the school, but are there also competitive concerns?

SG: For some yes, for some no. Some universities have asked their faculty to take a pause and not engage in any type of relationship like this, but some universities embrace it. Several students who have taken our course have sent us messages saying they are now going to apply to a full-time MBA program because they see the value and they want the certification. So I’m not sure it’s purely complimentary, but it’s also not purely competitive.

TC: What is your economic relationship with these professors?

SG: I’m not going to disclose the exact economic agreement. What I will say is that we see attracting these superstars and retaining them as key to our value proposition. And so our aim is that this is the greatest compensation per podium hour that they’re going to receive. If you have a course with 800 people, and they’re each paying $800, that’s $640,000. As you can imagine, there is a lot of gross margin capital that can be deployed or can be paid to the professor.

TC: Are most of the students gravitating to this platform coming from inside or outside of the tech industry?

SG: Fifty of the Fortune 100 [companies] have people who’ve taken our class so far, and it’s all walks. It’s pharma, it’s big AG, it’s big tech, it’s big oil. I would say we probably overindex in tech because these organizations are generous in terms of giving employees tuition remission, and I think, to a certain extent, my brand is bigger in the tech community and initially, that was kind of the awareness we had.

The other big cohort is middle-market companies, 10- to 500-people companies where a director there either didn’t have the opportunity or the inclination to go back to business school, but still would like a taste of supply chain from an MIT professor.

TC: What percentage of your students are outside the U.S.?

SG: I think it’s about 30% international. We have every continent covered.

We also try to reserve at least 10% of our class for scholarships. We have a rigorous scholarship process, where you send us an email saying you can’t afford it, and you get a scholarship. And a lot of our scholarships go to people internationally, because $800 in Rwanda is real money.

For more on Section4, including NYU’s relationship with Section4 and why Galloway raised what he did — and not three times as much — you can listen to our full conversation here.